The Storm and the Sonata

From the collection of short stories, Unusual Behavior, about a chemically sensitive woman's five-year long search for a home that doesn't make her sick.

The Storm and the Sonata

Warming up on that old, weathered Bösendorfer was a full hour-long workout. I could sense the battles it had seen, the countless hands that had poured into its keys before mine. There was something raw and resonant in its tone, as if grumbly old Beethoven himself still haunted its bones. However this storied instrument ended up in a little Episcopal church tucked in the mountains of Western North Carolina, I was honored to be its next partner in music-making. I approached it with full confidence in my ability and deep appreciation for the legacy I was stepping into—hoping to not only live up to it, but to add something of my own.

At the far end of the thick, alligatored case, a deep jagged gash told the tale of sudden and very loud drop which must have sent up an ungodly howl when the monumental crash occurred. I was astonished when I first saw it, as no one seemed to have been called in to repair it. Incredibly, the harp withstood the jolt, while it’s action remained as stubborn and as German as anyone would expect of its heritage.

The Beast and I slowly made friends. I was chasing a technique that I’d acquired long ago as an undergraduate in Dr. Roy Hamlin Johnson’s studio at The University of Maryland. The neural pathways were cloudy, but not lost.

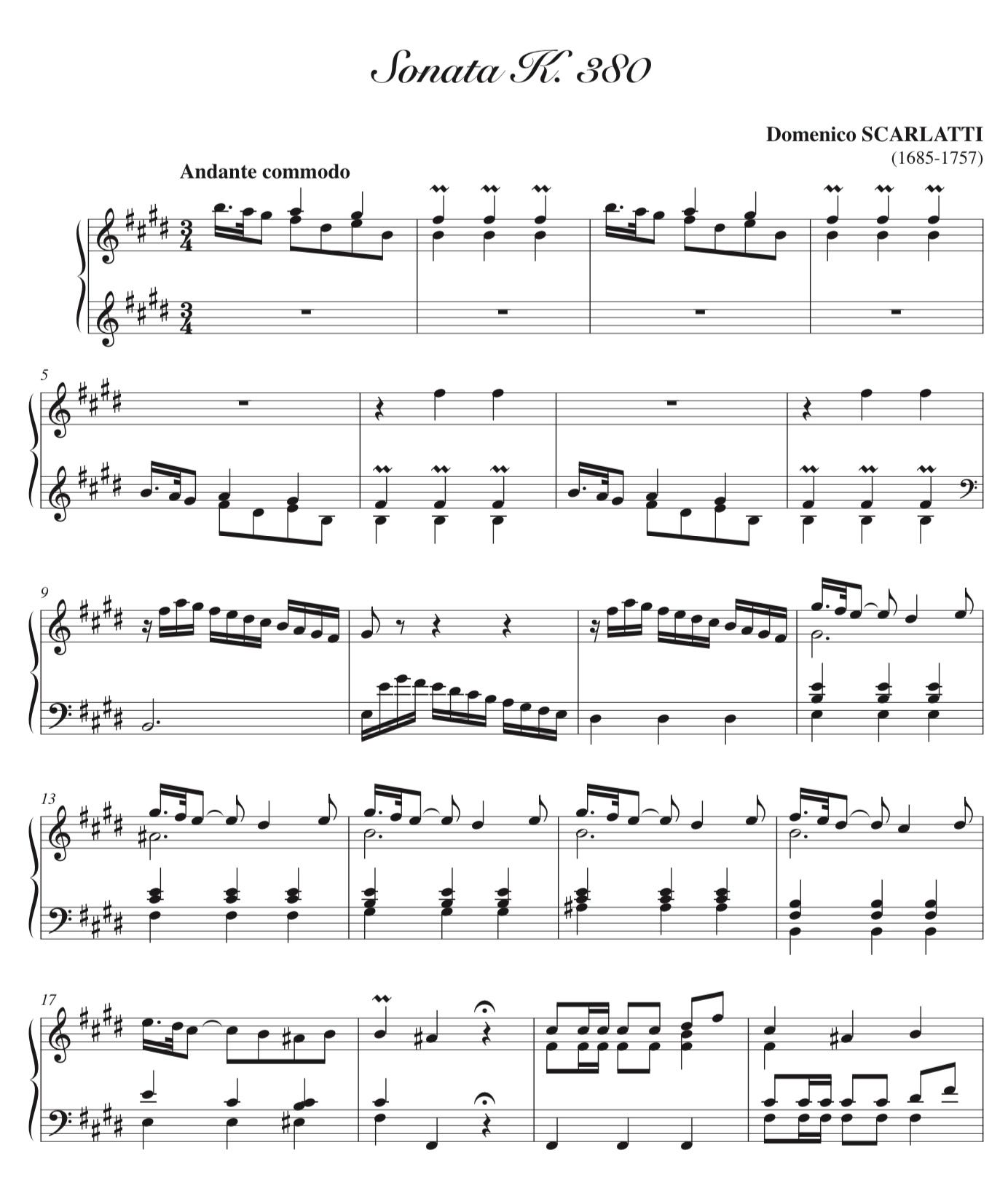

I chose Domenico Scarlatti, the Italian Baroque composer, to provide the map. His Sonata in E Major, No. 380 opened into luminous spaces, its elegant, playful figures inviting me to bring the piece to life. In his lifetime, Scarlatti composed over 500 harpsichord sonatas—many infused with guitar-like flourishes: resonant strums, cascading arpeggios, and rhythmic charm. While No. 380 isn't the boldest example of that technique, I could hear the intimacy of a guitar in each phrase, each embellishment, clear and bright—like frost softly breaking beneath a morning step.

I carried that image with me as I played—not with the raw energy of youth, but with something more open, more grateful in painting a landscape I’d never heard before.

Giving myself permission to interpret this elegant music as I chose seemed to excuse me from my usual job of writing music. I just couldn’t go there. I didn’t have the uncluttered brain space to invent new ideas with any amount of sequential purpose, so I didn’t try. It wasn't time.I wondered how great composers wrote symphonies during a war until someone told me, “They write because of the war.”

For now, I was finding refuge in the finely crafted music of others. It wasn’t just beauty—it was sanity. A structure to hold onto when the rest of my life slid perilously sideways. In many ways, the creative process, realizing the music through another composer or composing it myself, was nearly the same.

The day had started on a much more mundane note, however. I hadn’t slept. For most of the night, I battled the demons haunting the old cottage I just rented - a two-room hideaway tucked in the trees in Flat Rock, NC. I scrubbed every surface, attempting to banish what lingering ghosts of tenants past remained. Vinegar, peroxide, baking soda, unscented soap—my chemical warfare. But the cottage refused to yield. If I shut the windows, the air turned sour. If I opened them, the scent retreated just long enough to fool me into thinking I could live there.

Still, I had a new job at the church, and I needed it to work. I’d already invested many hours into familiarizing myself with the Episcopal liturgy while also getting comfortable on that beast of a piano. My choir was small and very devout ... and, as if they could sense my need, devoted to me. The old tank of a piano, with its scars and bluster, was my podium.

By 10 AM, I’d already practiced for hours. I’d successfully ignored the cottage problem as long as I could. In a flash, I knew the time had come for me to make the call. I had just paid rent and a hefty deposit, but money couldn’t buy me what I needed from them. I left a message about being very sorry, but my health left me no choice but to break the lease.

I try to not drag anyone else into the tedium of finding a safe place for my chemically sensitive body – I’m often ridiculed or dismissed by those who find it handier to think I’m making it up. But it’s the landlords who hold the highest distinction in being complete assholes about this. On a good day, they seldom go out of their way to take anyone’s personal situation into account. Their rudeness is beyond anything transactional and hard to take, bordering on bullying. As much as I needed them to understand, I could feel some backlash headed my way.

By one o’clock, I’d straightened up the stack of music and left the church. I’d spend the remainder of the day packing my car. But, I had no idea where I’d be spending the night.

The drive through Hendersonville and into Flat Rock was bittersweet. I’d really tried to live there. As I pondered what clothes and sheet music I needed for the next morning, I slowly turned into the cottage lot. In the few days I’d been there, I hadn’t seen anyone else. All was peaceful. A dozen efficiency cottages bordered the big semi-circle gravel driveway/parking lot. All was calm.

I ascended the cabin’s three porch stairs and was immediately puzzled to find the front door unlocked. Twisting the knob and opening a crack, I was alarmed to hear a strange loud whooshing sound while, all at once, was hit by a strong chemical odor. My head started spinning in reaction. I looked in to discover the largest ozone generator I’d ever seen. It had been placed and turned on in the middle of the tiny cabin’s floor. I knew immediately what is was and promptly began flinging my belongings onto the porch.

I am familiar with the uses of ozone to clear the air. I own a small ozone machine and sometimes use it to zap lingering odors. But my use of it is infrequent and in minimal doses. I spend no time breathing the ozone gas - it’s not oxygen. In fact, any ozone machine removes oxygen from a space and converts it to a gas that neutralizes other air vapors. Hospitals use it to disinfect clean rooms and insurance companies use it to clear smoke contamination. It’s a gas that is both natural and man-made. But it can be damaging if breathed in directly. The odor is somewhat like chlorine.

My little ozone machine is for spaces up to 1500 feet and has a minimal output to clear lingering airborne odors within about fifteen minutes. The ozone machine sitting on the floor in the cabin was twenty times the output, if not more. It's use in that small room was overkill. I didn’t know how long it had been on or why it was there without my permission in the first place.

Ozone will permeate any porous material, like clothing. I instantly was aware that any plan to sleep in my car that night could not include anything from the cottage – all of my clothes were contaminated.

During the frenzy of throwing my belongings onto the porch, the landlord appeared.

He screamed, “What are you doing here? I sent you a text!”

I had no kind words for this man as I battled on to try and save my belongings. The fact that he’d come into my space to do it in the first place was trespassing.

He watched me for a time, blinking, saying nothing.

I sternly remarked, “Am I dancing well enough for you?” I stared viciously at him.

I moved closer and shouted, “I know exactly what this is and you are contaminating everything I own. I don’t give a damn about your text.”

It’s difficult for me to remember exactly what happened next since my head was exploding from the gas. My lungs were on fire. My eyes felt burnt into my skull.

I think he stood there watching me for a while longer. I might have told him to get the fuck out. He never turned off the machine, afraid to enter the room himself.

As I drove away, I became aware that I had no next logical step. I remember monitoring the effects of the massive exposure - my headache, the swirling brain fog and my aching, burned out lungs and eyes. I needed fresh air and water.

I had a storage unit and took time to pull off the road to dump the bags after sorting through to find something to wear the next morning at 8 AM when I needed to be at work.

Another chemically sensitive woman, with whom I’d worked in the past few months, had been helping me find a safe place to live. Professionally, she was an excellent editor and had trained me to write magazine articles. I knew I could ask her to research anything. She was quick and intelligent, but unfortunately deeply mired in a co-dependent relationship with her long time boyfriend. Her tribe included a mother and her son and his girlfriend, all who did not believe her chemical sensitivity was real. My friend refused to acknowledge the complex danger she was in or how codependency held her family together in complete dysfunction. Every day, she described the inevitable emotional twists and turns brought on by her family’s gaslighting and about the barrage of chemical fragrances entering her home from a neighbor’s laundry. I spoke with her repeatedly about how to try and make her place safer and to consider the damaging effects of codependency. Over the months, I realized she may have wanted to leave her situation, but perhaps she was content with living vicariously through me. Perhaps she was alarmed by the gauntlet of errors and mishaps that had happened to me and couldn’t get beyond it. In any case, I had trouble sympathizing with her—but I needed her help.

She immediately began searching for any safe place I could spend the night. Hotels were out, Airbnbs, too expensive. HipCamp, an online platform that allowed anyone with a piece of land to charge $50 a night to any stranger, had become popular,

A few weeks earlier, I had spent a few nights with an Asheville family – I knew I could call them. But their home was a crazy mess. The husband, the wife, four wild homeschooled kids and their handyman all lived together on a couple acres in West Asheville. I remembered that the husband worked for a nonprofit dedicated to providing services for the homeless, but simply shook his head when he learned I was chemically sensitive.

I called them and received a resounding positive response to come to their home. At least I could get a shower and, maybe, settle down in the back seat of my car.

I arrived at their homestead and carefully navigated around the old cars and trucks that were piled up, rotting in a cluttered heap in the rutted up front yard. Dirty tires, tools and other undefined junk were scattered everywhere. I knocked timidly and brought on a parade of cats before I was let into a jumble of activity that was going on. The kids were busy in their own worlds, buzzing around like insects at a lightbulb. The man of the family barely looked up, more interested in cranking up a gas-fired hedge trimmer and going at it in the remaining afternoon light. Further off, a bonfire erupted, sending black smoke into the late afternoon sky. The woman, central to this rainbow of an other-world, was preparing a meal for everyone.

At any other time, I might have found this Felliniesque scene intriguing, but, on that one particular night, I stood paralyzed in the chaos knowing the gas fumes and the black smoke would soon reach me. I was already in bad shape. I tried to explain, but my words got lost in the hubbub, each person taking part in a fierce “do whatcha wanna do” scene. Yikes.

With an expression of controlled angst, I mentioned that I would be sick if I stayed. No one heard me. There was nothing that could help me there. I waved and left.

The crazy circus was shifting; night would be the backdrop of the next horrific act.

I called my friend in New York again. She’d been talking to the hip camper host who invited me to an Asheville-styled hippie gathering on his camp property. My friend urged me to pull over and step through the online reservation procedure with my debit card right away. I protested sternly since I knew 1campfires would be central to any of the Saturday night festivities. Asheville hippies are of a breed I’d long outgrew – whatever was happening there would last all night. I wanted no part in it. But, my friend insisted. I realized that she wanted me to be around other people.

In a state of complete frustration, I pulled into an desolate K-Mart parking lot and tried to locate my wallet and phone. The madness had no end. I got out and walked around the car a few times to let off some steam, only to then realize I was being watched. At a fairly close range, about thirty feet away, a man had stopped in a beat up car and was taking in everything I was doing. His grayed head was barely visible above car door. His expression didn’t change when he saw that I noticed him,

That was it. For God’s sake. enough. In moments of real danger, I know what to do. It takes an immediate shedding of any other thought, being entirely present and acting to save only one life – mine. I weighed the danger in a split-second, calmly slid into the drivers seat, held my phone to my ear and steadily, slowly drove off.

He followed me.

Fuck.

I knew the terrain, the back streets and alleys of the area. I deliberately motored through a red light, hoping a policeman would appear, then turned into a hilly West Asheville neighborhood. I wound around a church parking lot, down a couple well lit streets, and finally to the entrance of Mercy Urgent Care. I waited under a street light, my keys, phone and bear spray in my hand, ready to bolt for the door. But I didn’t want the man to have followed me and still be lurking when I came out. So, I waited, ready to punch in 911 at any moment.

An hour later, the urgent care place began closing up. People walked to their cars. The parking lot lights stayed on.

I had been trying to tell my friend what had happened, but she’d talked to the HipCamp host again and insisted I make the reservation that moment. In her mind, being around other people was the answer, while, in my mind, I was doing everything to get away from them. Nevertheless, I pawed at the clutter in the passenger seat until I felt my wallet. Angry and tired, I fumbled in the wallet and my purse for a while, only to discover the card was gone. Of course it was. I knew instantly that it was on the ground in that forsaken K-Mart lot. I’d dropped it when I saw that I was being watched. Or maybe that dude was trying to give me back my card. Who knew?

I sternly told my friend that I would not be calling the HipCamp host. The issue was closed. I knew the parking lot at Cracker Barrel was nearby and I could stay there. It was a busy spot, just under a Route 40 cloverleaf with many big rig trucks crisscrossing between the off ramps, the gas stations and late night fast food restaurants.

The moon was high in the sky when I turned west on Smokey Mountain Parkway towards Canton. The fast food signs towered over the humid, exhaust-filled scene. I arrived and saw several cars parked with some decent privacy space between them. A police car was parked just out of view, but with enough presence that it made all the difference to me.

I sat motionless in my chosen spot for a long time before deciding to get in the backseat. Awkwardly, I climbed over, not wanting anyone to see me outside of the car. I rummaged around in the back of my car long enough to figure that it was as good as it was going to get.

Looking for ways to be more comfortable, I thought about cracking the windows. The move meant I would need to either climb over the seats twice again or step quickly out and into the car to get to the controls. I calculated the move and chose the latter. I would be quick. Other people were around, but they seemed as self-absorbed as I was. Who would notice? Be cool.

I opened the back driver’s side door and stood upright in the night air. Taking a full breath in, I was suddenly seized by a ghastly wave of urine odor. My stomach lurched.

I moved to the driver’s door, let myself in, closed the door gently. I couldn’t stay. It was horrible.

Calmly, I secured my reacting body into my seat belt and turned the key. I drove off slowly and headed to the church, twenty-five miles away. When I arrived, I could see fog blanketing the valley meadows in the moonlight and felt relieved in the solitude. I unlocked the church door and carried in my belongings. In the bathroom, I removed all of my clothes, stood naked at the sink and washed my body and hair. I got dressed.

I thought about my friend who I knew collapsed in bed every night, weary of the constant doubting and belittling by those who she wanted to be her family. She often spun her stories into testaments of belonging, citing Christmases, birthdays as times she felt especially hurt. Yes, I get it. But, I knew her journey to a safe place would be plagued by false expectations until she could claim her authentic self. She cried often. I was sorry for her. I didn’t know if she would be able to leave her situation. I was weary of allowing her or anyone to feed off my courage as a simple observer.

Standing alone in the church bathroom, I felt the strength I needed rooted in my power to say “no.” I owned the strength to always leave if I needed. Nothing was as important as the unshakeable faith I had in myself.

At 3 AM, I started practicing.

At 9 AM, I played the sonata for a congregation-filled church.

Carol, thank you for sharing your incredible experiences and writings. I was half way through reading this piece and remembered that is non-fiction.

There are very few people who will understand what challenges we face with chemical sensitivities. Your writings will help bring understanding and awareness to the obstacles of a life with multiple chemical sensitivity. Thank you ~